Iterators in C#

Publish date: 2021-04-22

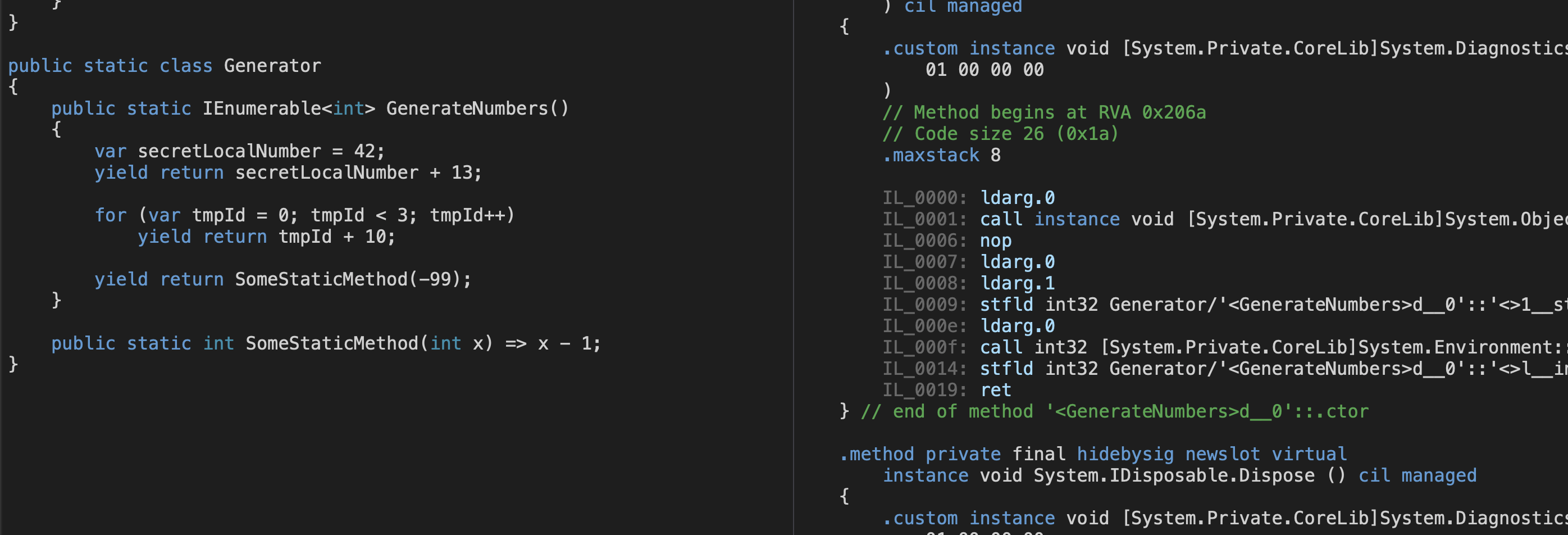

Iterator IL code

Intro

Main goal of this post is to present how iterators actually works in C#. In particular we will take a look on IL (Intermediate Language) generated by the compiler to check out what is really going on.

But first let's start from loosely stated definition of iterators in C#.

An iterator is a method or property which returns IEnumerable<T> or

IEnumerator<T> and uses yield return or yield break contextual keywords.

One could ask what is then a difference between an iterator and a method that

returns IList<T> which also satisfies IEnumerable<T> interface? The main

difference is the way of consumption of those sequences. In case of IList<T>

actual memory is allocated for all elements. In case of iterators we are

dealing with so-called lazy evaluation. Object from the sequence is taken only

when it's needed.

To express this difference let's consider the following silly example:

public static IEnumerable<int> PrepareNumbers(int n)

{

var numbers = new List<int>(n);

for (var i = 0; i < n; i++) {

numbers.Add(i + 13);

}

return numbers;

}

public static IEnumerable<int> GenerateNumbers(int n)

{

for (var i = 0; i < n; i++) {

yield return i + 13;

}

}const int size = int.MaxValue;

var numbers1 = PrepareNumbers(size);

var numbers2 = GenerateNumbers(size);

Method PrepareNumbers allocates in this case over two billions ints so it

should throw System.OutOfMemoryException on systems with 8GB of RAM or

smaller. But that is not a case for GenerateNumbers because iterator doesn't

perform any allocation for their elements. How C# compiler is doing that? There

can be (almost) any C# code within the iterator method. So how in fact C#

compiler know how to prepare the sequence without preallocation? Let's found

out.

Consumption of IEnumerable<T>

Before we jump into details of iterator blocks I wanted to make sure we are all

familiar with the fact how actually foreach is consuming sequence of

IEnumerable<T>.

foreach (var item in sequence) {

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

The above loop over all elements in the sequence is just syntactic sugar for

the following:

using (IEnumerator<T> enumerator = sequence.GetEnumerator()) {

while (enumerator.MoveNext()) {

var item = enumerator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

}

In each loop iteration the MoveNext() method of enumerator is called and

current element is taken using Current property. Based on this we can suspect

that all of iterator "magic" is behind MoveNext() method.

Internals of iterators

To study internals of iterators let's focus on single static method with iterator block.

public static IEnumerable<int> GenerateNumbers() {

var secretLocalNumber = 42;

yield return secretLocalNumber + 13;

for (var tmpId = 0; tmpId < 3; tmpId++)

yield return tmpId + 10;

yield return SomeStaticMethod(-99);

}

Iterating over GenerateNumbers() result would produce the following sequence

-100 (assuming that SomeStaticMethod decrease its argument

by one).

In order to look into the iterator block we will take a look on IL generated by C# compiler. IL can be generated based on .NET binaries using ildasm.exe tool on Windows or monodis on Linux and macOS. For small examples very convenient way to look at IL based on C# code is online service sharplab.io. If you're not familiar with IL here you can find table of instructions with short description. Disclaimer: in the following IL listings I simplified names of objects to make those more readable. However it's not identical with generated IL.

Let's start from the very top and find out what is under the hood of

GenerateNumbers method.

IL_0000: ldc.i4.s -2

IL_0002: newobj instance void _GenerateNumbers::.ctor(int32)

IL_0007: ret

Those three instructions creates new object of class _GenerateNumbers using

constructor with value -2. Interesting! As it turned out C# compiler generates separate

(nested, private, sealed) class for GenerateNumbers() method. This class is

of the following form

private sealed class _GenerateNumbers

: IEnumerable<int>, IEnumerator<int>, IDisposable

{

private int _state;

private int _initialThreadId;

private int _secretLocalNumber;

private int _tmpId;

public int Current { get; }

public _GenerateNumbers(int state) { }

public void Dispose() { }

public bool MoveNext() { }

public void Reset() { }

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator() { }

public IEnumerator GetEnumerator() { }

}

Set of interfaces which generated class satisfies isn't surprising. What was

interesting to me is the fact that this generated class captures all local

variables from original method GenerateNumbers().

As we saw earlier two methods are especially important GetEnumerator() and

MoveNext(). The first one is executed once per consumption to get

IEnumerator<T> however MoveNext() is heavily used - in each iteration.

Next we'll take a look on GetEnumerator() but we'll mostly focus on

internals of MoveNext() method.

GetEnumerator() method

This methods returns an instance of _GenerateNumbers class with set _state

pseudo code is as follows

if (_state == -2) {

return new _GenerateNumbers(0);

}

if (_initialThreadId != get_CurrentManagedThreadId()) {

return new _GenerateNumbers(0);

}

_state = 0;

return this;

So eventually we end up with an instance of _GenerateNumbers with set

_state = 0. The only difference is whenever we can use existing instance or

produce the new one. Finally after the line

using (var enumerator = GenerateNumbers().GetEnumerator())

object enumerator is the instance of _GenerateNumbers (the generated class)

with _state set to zero. Now we can proceed to using our enumerator to

iterate over the sequence using MoveNext() method. Let's dive deep into this

crucial part.

MoveNext() method

As I stated before this is the method where the actual work is done. Generated IL code is a bit longer then in earlier examples, therefore we'll try to break it into parts.

Let's start from the observation that this method has three local variables

.maxstack 3

.locals init (

[0] int32,

[1] int32,

[2] bool

)

The method starts from branching based on field _state:

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_0006: stloc.0

IL_0007: ldloc.0

IL_0008: switch (IL_001f, IL_0021, IL_0023, IL_0025)

IL_001d: br.s IL_002a

IL_001f: br.s IL_002c

IL_0021: br.s IL_0054

IL_0023: br.s IL_007c

IL_0025: br IL_00b6This listing can be translated into

- load local variable

[0]onto the stack - load field

_stateonto the stack - store

_statein local variable[0] - load local variable

[0] - go to location based on local variable

[0]

Instruction br.s <target> branches to <target> location. At the beginning

(after the initialization) value of _state field is equal to zero. Let's than

examine code starting from location IL_002c.

IL_002c: ldarg.0

IL_002d: ldc.i4.m1

IL_002e: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_0033: nop

IL_0034: ldarg.0

IL_0035: ldc.i4.s 42

IL_0037: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_secretLocalNumber

IL_003c: ldarg.0

IL_003d: ldarg.0

IL_003e: ldfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_secretLocalNumber

IL_0043: ldc.i4.s 13

IL_0045: add

IL_0046: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_current

IL_004b: ldarg.0

IL_004c: ldc.i4.1

IL_004d: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_0052: ldc.i4.1

IL_0053: retLet translate this block to English

- set

_state = -1 - set

_secretLocalNumber = 42 - set

_current = _secretLocalNumber + 13(our first yield return) - set

_state = 1 - return

1 (true)

OK, so at this point MoveNext() has returned true and set _current =

_secretLocalNumber + 13. Therefore when the value from enumerator will be

consumed in the first iteration of the loop enumerator will pass current value

of _current field which is 55. That's exactly what we wanted.

In GenerateNumbers() method the step would be to yield return from the

for loop. Let's take a look how next call of MoveNext() will handle that.

Now _state = 1 so based on initial branching now we have to start from

IL_0054 location.

IL_0054: ldarg.0

IL_0055: ldc.i4.m1

IL_0056: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_005b: ldarg.0

IL_005c: ldc.i4.0

IL_005d: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_tmpId

IL_0062: br.s IL_0093

This block starts from setting _state = -1 and _tmpId = 0. At the end there

is branch to IL_0093. Block starting from IL_0093 check bound condition on

_tmpId. If _tmpId < 3 then branches to IL_0064. Otherwise it continues.

At the moment _tmpId = 0 < 3 so we should continue from IL_0064.

IL_0064: ldarg.0

IL_0065: ldarg.0

IL_0066: ldfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_tmpId

IL_006b: ldc.i4.s 10

IL_006d: add

IL_006e: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_current

IL_0073: ldarg.0

IL_0074: ldc.i4.2

IL_0075: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_007a: ldc.i4.1

IL_007b: retIn the above block the following happens

- load

_tmpIdonto the stack - load short integer

10onto the stack - add

_tmpIdand10and store in_current(our second yield return) - set

_state = 2 - return

1 (true)

In this iteration MoveNext() returns true with _current = 10, _state =

2 and _tmpId = 0.

On the next MoveNext() call we will start with _state = 2 which means

location IL_007c based on initial branching. Generated IL code is almost

identical as in the previous listings so I'll summarize this in the following

steps

- Field

_tmpIdis incremented by one - Bound check is performed

- Whenever

_tmpId < 3we will jump toIL_0064and the previous listing will happen - While we are inside

forloop the state of_statefield will remain constant with set value2

Based on this we now know exactly how lazy evaluation is done in case of loops.

Our generated class keep the information which iteration was performed last

time MoveNext() was called within _tmpId variable.

At the end let's take a look what happens when _tmpId = 3 and for loop is

done:

IL_00a0: ldarg.0

IL_00a1: ldc.i4.s -99

IL_00a3: call int32 SomeStaticMethod(int32)

IL_00a8: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_current

IL_00ad: ldarg.0

IL_00ae: ldc.i4.3

IL_00af: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_00b4: ldc.i4.1

IL_00b5: ret

Basically nothing new. Static method SomeStaticMethod is being called with

parameter -99 and the result is stored inside _current field. Field

_state is set to 3 and method returns true.

Finally when the MoveNext() will be called again the method will start with

_state = 3. So we will start from IL_00b6 location:

IL_00b6: ldarg.0

IL_00b7: ldc.i4.m1

IL_00b8: stfld int32 _GenerateNumbers::_state

IL_00bd: ldc.i4.0

IL_00be: ret

Internal _state is set to -1 and the method returns 0 (false) therefore

next iteration would not happen.

Performance

After our rather detailed analysis of MoveNext() method I thought about

performance of using iterators. Looping over a collection would call

MoveNext() frequently and as we saw earlier that would cause many jumps just

to get single element in lazy fashion. I'm worried that this behaviour might

causes many CPU cache misses and decrease performance.

This is not post about performance but I've decided to make a simple benchmark to check what would be the cost of iterating over simple integer collection just to sum its values.

I've benchmarked three methods:

- Sum numbers by iteration using

forloop overList<int>using indexes - Sum numbers by using

foreachloop overList<int> - Sum numbers by using

foreachloop overIEnumerable<int>created by iterator block

Source code of this benchmark can be found here.

I have run this benchmark on Mac M1 with ARM CPU architecture and on my desktop with Linux.

Results on Mac M1 (ARM)

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.12.1, OS=macOS 11.2.3 (20D91) [Darwin 20.3.0]

Apple M1 2.40GHz, 1 CPU, 8 logical and 8 physical cores

.NET Core SDK=5.0.202

[Host] : .NET Core 5.0.5 (CoreCLR 5.0.521.16609, CoreFX 5.0.521.16609), X64 RyuJIT

DefaultJob : .NET Core 5.0.5 (CoreCLR 5.0.521.16609, CoreFX 5.0.521.16609), X64 RyuJIT| Method | Size | Mean | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|

| SumByIndexes | 1000 | 2.507 ns | - |

| Sum | 1000 | 30.659 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 1000 | 1,559.437 ns | 328 B |

| SumByIndexes | 1000000 | 4.965 ns | - |

| Sum | 1000000 | 25.535 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 1000000 | 1,550.568 ns | 328 B |

| SumByIndexes | 10000000 | 3.064 ns | - |

| Sum | 10000000 | 23.035 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 10000000 | 1,557.213 ns | 328 B |

Benchmark results on Mac M1 (ARM)

Results on Linux (x86)

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.12.1, OS=ubuntu 20.04

AMD Ryzen 7 3700X, 1 CPU, 16 logical and 8 physical cores

.NET Core SDK=5.0.200

[Host] : .NET Core 5.0.3 (CoreCLR 5.0.321.7203, CoreFX 5.0.321.7203), X64 RyuJIT

DefaultJob : .NET Core 5.0.3 (CoreCLR 5.0.321.7203, CoreFX 5.0.321.7203), X64 RyuJIT| Method | Size | Mean | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|

| SumByIndexes | 1000 | 1.851 ns | - |

| Sum | 1000 | 20.135 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 1000 | 1,457.868 ns | 328 B |

| SumByIndexes | 1000000 | 1.836 ns | - |

| Sum | 1000000 | 20.610 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 1000000 | 1,461.925 ns | 328 B |

| SumByIndexes | 10000000 | 1.877 ns | - |

| Sum | 10000000 | 19.509 ns | 40 B |

| SumEnumerable | 10000000 | 1,479.415 ns | 328 B |

Benchmark results on Linux (x86)

Benchmark Summary

Iterating over the list (actually allocated contiguous block of memory) using

foreach loop is over fifty (50x) times faster then using iteration over actual

iterator (lazy evaluated). My best guess is, based on our IL code analysis,

it's because of CPU cache misses in case of the iterator.

What's also interesting is the cost of using foreach over for loop.

But it shouldn't be surprising by now. As we saw earlier foreach once call

GetEnumerator method and on each iteration call MoveNext() method. An

actual method. Whereas for loop just increment index and take data from

underlying array directly.

Another interesting point is difference between CPUs (M1 vs faster Ryzen).

Method Sum took about 30ns on Mac M1 and about 20ns on Ryzen which is

around 33% improvement. In case of iterating using iterator the difference is

much smaller around 1550ns versus 1470ns which is around 5%. This is

another point which suggest importance of CPU caches. It is probably not used

(at least not used efficiently) in case of iterator and is definitely used in

case of List<T>.

Summary

In summary iterators produces lazy evaluated sequences by generating a class in

compile time which captures state of iterator block in order to produce next

element within MoveNext() method. I hope this post helped you to better

understand how it really work.

Also let's not forget about the fundamental trade off - memory space versus

performance. Using Linq extension methods makes IEnumerable<T> very easy and

fun to operate on but after this post I'll be always conscious about the cost.

I think next step after this post might be to look closely at the Linq extension methods implementation. Now this should be much easier, once you know how iterators works. Implementation of all methods are placed in single file System/Linq/Enumerable.cs.